Deserts can take many forms—including sweeping sand dunes, rocky canyons, sagebrush steppes, and polar ice fields. But they are united by one thing: lack of precipitation. Generally speaking, anywhere that receives less than 10 inches (25 centimeters) of rain per year is considered a desert, said Lynn Fenstermaker (opens in new tab)an ecologist at the Desert Research Institute in Reno, Nevada.

Of course, the lack of rain means the deserts are dry. But why do some places on Earth get much less rain than others? In other words, why are deserts dry?

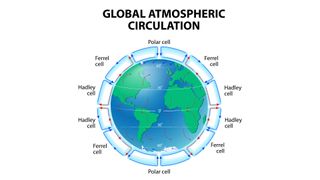

Global air circulation patterns are the biggest reason, Fenstermaker said. Solar energy hits the earth most directly at the equator, heating the air and evaporating moisture from it. The warm, dry air rises and travels towards the poles. It tends to drop again around 30 degrees latitude, Fenstermaker explained. This circulation pattern is called a Hadley cell, and it drives the trade winds, which fueled early exploration of the world by seafaring explorers. This is also why many of the world’s largest deserts — such as e.g Sahara and the Gobi in the Northern Hemisphere and the Kalahari in the Southern Hemisphere—are at these midlatitudes.

Related: Can the Sahara ever turn green again?

But the story is more complicated than that. Wind patterns interact with topography to influence where deserts are found. For example, air sweeping in from the ocean and hitting a mountain range will release its moisture as rain or snow onto the slopes as the air rises. But when the air crosses the mountains and descends on the other side, it is dry. In California, for example, the Mojave Desert is in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada, Fenstermaker said.

Sometimes inland areas are drier because they are so far from a large body of water that air blowing in has lost all its moisture by the time it arrives, said Andreas Prein (opens in new tab), an atmospheric scientist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in Boulder, Colorado. Such is the case with the Gobi Desert in Central Asia, which is also protected by the Himalayas.

On the other hand, coastal does not always mean wet. Cold ocean currents colliding with air moving into the coast can create fog. When that fog moves over land, the moisture stays in the air instead of falling as rain. This can create deserts bordering the sea, such as Atacama in Chile, one of the driest places on earth.

Not all deserts are hot either; parts of the Arctic and Antarctic count as deserts. Cold air can’t hold moisture as well as warm air does, Prein said. So the freezing temperatures at the poles lead to very little precipitation, even though plenty of water is stored in the ground as ice.

As global climate patterns change, so do the deserts. For example, thousands of years ago, The Sahara was covered in grasslands and tropical forests (opens in new tab). And today, climate change is reshaping the boundaries of deserts around the world.

“The Hadley cell is expected to spread north and south due to climate change,” Prein said, expanding the zone ripe for desertification. Warmer temperatures can accelerate the shift by increasing evaporation of water and further drying the air. Beyond just precipitation, it’s the balance between precipitation and evaporation that defines a desert, Prein added.

“Globally, with warming, what we expect is that we’re going to have more evaporation and just expansion of existing desert regions,” Fenstermaker noted.

Human pressure on the landscape also contributes. Cutting down trees to plant crops removes native vegetation, and some research suggests that deforestation in the tropics reduces rainfall (opens in new tab). If more water evaporates instead of being retained in the soil by plants, a feedback loop pushes the landscape drier and drier. Semi-arid areas on the fringes of existing deserts are particularly vulnerable.

“It’s often a combination of factors that help deserts grow,” Prein said. “It’s not just human activity, or climate change, or the natural climate variability, but it’s everything on top of each other that is pushing the ecosystems over the tipping point.”

#deserts #dry